|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Learn Hebrew |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What is the Oral Torah? |

|

Traditional Judaism believes that when Moses was on Mount Sinai for 40 days and nights writing down the words of the Torah, God also provided him with additional explanations that were not explicitly incorporated into the written text. This additional commentary and elucidation of the written Torah is called oral Torah, or Torah she'bal peh (תּ×Ö¹×¨Ö¸× ×©×Ö¶×Ö¼Ö°×¢Ö·× ×¤Ö¼Ö¶×â) [from al peh, "by mouth"]. The words that Moses finally committed to writing in the Torah scroll (ספר ת×ר×) is called Torah shebikhtav (ת××¨× ×©××ת×). According to this view, there were actually two Torahs given to Moses on Sinai: the written Torah and the oral Torah, and together these are considered the full revelation of the Torah. Maimonides, a chief spokesman for this brand of Judaism, wrote: "Every commandment which the Holy One, blessed be He, gave to Moses our teacher, was given with its clarification. First, he told him the commandment (Written Torah) and then he expounded on its explanation and content including all that which is included in the Torah" (Commentary on the Mishnah). |

|

|

The Early Jewish Sages |

|

|

|

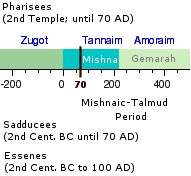

The sages of Jewish tradition also include the Zugot (142-40 BC), five "pairs" of leaders who established schools and were instrumental in the activities of the Sanhedrin. Zugot always stood at the head of the Sanhedrin -- one as president ("nasi") and the other as vice-president or father of the court. The last pair of Zugot was Hillel and Shammai during the time of King Herod the Great (c. 74-4 BC). |

|

The Shift to Post-Temple Judaism |

|

It's important to understand that the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD caused a catastrophic upheaval for the Jewish people. How could the sages understand Judaism and practice their faith apart from the rituals and sacrifices offered by the priestly service? With the Temple gone, who would be the religious authority for the Jewish people? Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai (a former pupil of Hillel) left Jerusalem after the Temple was destroyed and founded a new center of Jewish learning in Yavneh. The Council of Yavne (70-90 CE) subsequently "reinvented" Judaism by 1) decreeing that animal sacrifices and Temple rituals could be replaced by prayer and good deeds (mitzvot); 2) rejecting the Septuagint translation of the Scriptures and establishing the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures; 3) adding the so-called Birkat HaMinim to the daily prayers at synagogues (this "blessing" required a curse to be recited upon the minim (heretics), understood primarily as Messianic Jews). The outcome of all this was that Rabbinical Judaism would become the mainstream religious system of post-Diaspora Judaism.

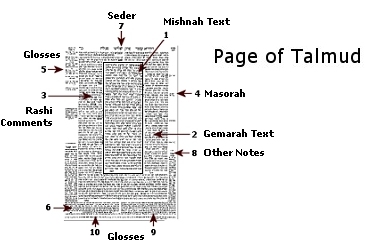

After the Mishnah was published it was studied exhaustively by generations of rabbis in both Babylonia and Israel. Over the next three centuries additional commentaries on the Mishnah were compiled and put together as the Gemara. Actually there are two different versions of the Gemara, one compiled by the scholars in Israel (c. 400 AD) and the other by the scholars of Babylonia (c. 500 AD). Together the Mishnah and the Gemara form the Talmud, but since there are two different Gemaras, there are two different Talmuds. The Mishnah with the Babylonian Gemara form the Talmud Bavli and the Mishnah with the Jerusalem Gemara form the Talmud Yerushalami (Jerusalem Talmud). Since the Gemara functions as a commentary to the Mishnah, the orders of the Mishnah form a general framework for the Talmud as a whole (however not every Mishnah tractate has a corresponding Gemara).

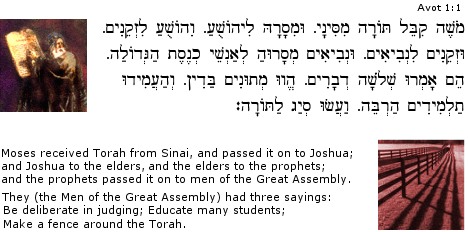

With the rise of Rabbinical Judaism Torah came to mean something far more than the written words of Moses. The oral Torah was considered a legally binding commentary on the written Torah, interpreting and explaining how its commandments are to be carried out. The quote from Pirke Avot 1:1 is part of the reinvention of post-Temple Judaism wherein the religious authority is said to have passed from Moses, to Joshua (by semikhah), through various generations of elders, and eventually to the Rabbis themselves. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Case for the Oral Torah |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Is there a case to be made for the existence of the oral Torah? Yes, of course. First it should be noted that the oral Torah is sometimes considered to be more basic than the written Torah of Moses. It is argued that since God first spoke the Ten Commandments to the Jews before Moses ascended Sinai to get the details, oral Torah actually preceded the giving of the Torah at Sinai. The same point can be made, incidentally, regarding God's instructions given to Adam, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, and even Moses himself before he was commanded to write down the laws for Israel given on Mount Sinai. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Questions and Concerns |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now that we have heard the arguments for the validity of the oral Torah, what are we to make of them, especially as Messianic Jews (and Christians)? Some questions include: Is the oral Torah to be considered as "divinely inspired?" Did Moses actually receive a divine commentary while up on the mountain? Does final interpretative authority rest with oral tradition and the rabbis? Did Yeshua and His followers accept the oral Torah? And what are we to make of some of the fabulous stories (and outright errors) we read in the Talmud and Midrash? Are such stories and imaginative interpretations of the written Torah to be taken seriously, and if so, in what way? Finally, what about the Kabbalah (the "third" or "hidden" Torah and mystical traditions? Are these also part of the oral Torah? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jesus and Oral Torah |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What about Yeshua (Jesus)? Did He support the idea of oral Torah? Well, yes and no. The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses' seat, so practice and observe whatever they tell you - but not what they do. For they preach, but do not practice. At first glance it seems that Yeshua is saying that His followers are to practice and observe the Jewish traditions as expounded by the scribes and Pharisees. However, when we closely read the context of this passage we note that these words undoubtedly indicate irony and scorn for their outward shows of righteousness (Matt 23:13-36). If Yeshua had seriously meant for His followers to practice and observe what the scribes and Pharisees had taught, why would He go on to berate them as hypocrites who "shut up the kingdom of heaven against men," making a "pretense" of their prayers and going out of their way to make one convert who is "twice the child of hell" than themselves? Would Yeshua have you and I practice and observe these sorts of things? On the contrary, the overall context of this passage indicates that the follower of the Messiah should not become subject to their authority. This interpretation is further made evident by Yeshua's statement that we are to be subject to Him alone as Teacher and are to call no one "rabbi" (Matt 23:8). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Paul and Oral Torah |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Apostle Paul likewise had a mixed view of the role of the authority of the oral Law. On the one hand we need to remember his training as a Rabbi when he quotes the Scriptures in his writings. Paul was at one time a student of Gamaliel the Elder, the grandson of the renowned Rabbi Hillel, and therefore familiar with the sages and their interpretations (Acts 5:34-40). For example, when he wrote, "And all drank the same spiritual drink, for they were drinking from a spiritual rock which followed them; and the rock was Christ" (1 Cor. 10:4), he was quoting from a story later recorded in the Talmud (i.e., that from the time that Moses struck the rock at Horeb and brought forth water until the death of Miriam (Exod. 20:1), this water-giving rock "followed the children of Israel through the desert and provided water for them each day" (Taanit, 9a and Bava Metizia, 86b)). In addition Paul was careful to observe various Torah restrictions during his life. Even after his conversion, he took the Nazirite vow (Acts 18:18), lived "in observance of the Torah" (Acts 21:23-24), and even offered sacrifices in the Jewish Temple (Acts 21:26). Paul asked, "Do we then nullify the Law through faith? May it never be! On the contrary, we establish the Law" (Rom. 3:31). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Karaites and Oral Torah |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Karaite Judaism rejects the authority of Rabbinical interpretations and the oral Torah because the Mishnah (i.e., the written down form of the oral Torah) quotes different opinions that contradict one another. Their words are those of men living in the 2nd-5th centuries AD. and their writings do not attest of divine authority like the prophets who speak "Thus saith the Lord," but rather "rabbi so-and-so said to rabbi so-and-so..." |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other Concerns |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contrary to the view that the complete written Torah was given to Moses at Sinai, it must be understood that only part of it was actually recorded at that time. Only the sefer habrit was written at the time of giving of the Ten Commandments at Sinai; the rest of it was compiled and written during the 40 years in the desert. In response, R. Eliezer said to the Sages, "If the Halakhah agrees with me, let it be proved from heaven." Sure enough, a divine voice cried out, "Why do you dispute with R. Eliezer, with whom the Halakhah always agrees?" R. Joshua stood up and protested: "The Torah is not in heaven!" (Deut. 30:12). We pay no attention to a divine voice because long ago at Mount Sinai You wrote in your Torah at Mount Sinai, `After the majority must one incline'. (Ex. 23:2)" The revisionism of the Talmud ascribes sole authority to the rabbis in Jewish life. Rabbinical consensus and interpretation now trumps all. Perhaps this explains why it is so difficult to share the gospel message with practicing Jews today. To point out how Yeshua is revealed in the Torah, the Writings, and the Prophets (i.e., the Tanakh) is often met with a "screening" mentality: Every prooftext in the Hebrew Scriptures will be given an alternative interpretation that accords with the Yeshua-rejecting Rabbinical tradition... In other words, since the rabbis have not accepted Yeshua as Israel's Mashiach, that's the final word on the subject. Perhaps the "fence around the Torah" was intended to restrict access to the plain sense of Scripture, thereby hiding from view that Rabbinical authority itself is without sanction from the written Torah. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Relative Importance of the Oral Torah |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Despite these serious objections to the idea of oral Torah as a source of divine authority, we need to ask if there is any value for us to study Talmud and the oral traditions? Yes indeed, especially since the Talmud often provides invaluable insights into much of the written Torah, including many of the teachings and discussions about the meaning of Scripture that were prevalent at the time of Yeshua. The Talmud also provides details about the social life of Israel, the origins of various customs, and Temple activities that are not explicitly mentioned in the writings of Moses. Often additional insights from the Jewish sages make Scriptural passages clearer to the reader. Frequently the rabbi's knowledge of Hebrew, Aramaic, and even Greek shed new light on important words and grammatical constructions. The task of doing Messianic Biblical Theology would be unthinkable without consulting the collected wisdom of the Jewish Torah sages. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What about Aggadah and Midrash? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

But what about the various legends and midrashim about the Torah embedded within Jewish tradition? Are these to be taken seriously or to be disregarded as myth or nonsense? Now that we know what midrash and aggadic literature is about, let's take a look at some of the more popular aggadot (legends) that concern the giving of the Torah to Israel at Sinai, as well as some other stories about the importance of the Torah for the Jewish people. In charity to the authors of these stories, ask yourself how the story or legend supports other truths you understand from the written Torah. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Torah Offered to the 70 Nations |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A famous story (Peskita 21) says that from the time of creation until the time of the Exodus the LORD offered the Torah to each of the 70 nations, but they all refused it. For example, God came to the descendants of Esau and said to them, "Will you accept the Torah?" They asked, "Master of the universe, what's written in it?" He answered, "Do not commit murder." They replied, "This is the legacy our father left us; as it says, 'And upon your sword you shall live' (Gen. 27:40); therefore we cannot accept the Torah." God went from nation to nation and heard their excuses for not accepting Torah (He did this so that the nations might have no excuse to say, "Had the Holy one, blessed be He, desired to give us the Torah, we should have accepted it"). Finally the LORD turned to the children of Israel, the least of the nations, and asked them, "Will you accept the Torah?" They said to Him, "What is written therein?" He answered, "Six hundred and thirteen commandments." They replied in unison: Na'aseh venishmah - "All that the Lord has spoken will we do and be obedient" (Ex. 24:7). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

God as the Eager Groom |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Another story says that God originally planned to give the Torah to the Jews the day after they left Egypt -- but on second thought He decided to wait for fifty days. God wanted to make sure Israel would accept Torah for the right reasons -- not because of the miracles, signs and wonders He performed to secure their redemption from Pharaoh.... Other versions of this story have it that God delayed giving the Torah so as not to appear like a groom who jumps too hastily into marriage or because the people needed to be free from their defects (49 levels of tumah) before receiving the defect-free Torah. Therefore God healed all the sick of Israel between the Exodus and the arrival at Sinai. The journey to Sinai was likened to God "courting" His betrothed. God treated Israel as a king who properly wooed his beloved by showering her with many gifts (i.e., health, miraculous water and manna, the bread from Heaven). The Torah itself was God's ketubah (marriage contract) signed after the ceremony at Sinai. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

God Created the Universe for Israel's Acceptance of Torah |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Another midrash says that God created the universe solely on the condition that Israel would accept the Torah when it was offered to them. Should Israel refuse, God would return the world to tohu v'vohu (chaos and void, Gen 1:2). The very universe itself depended upon the Jew's acceptance of the Torah, and even today, the world is sustained on account of Lamed-Vav Tzaddikim (×"× ×¦××ק××) -- the 36 hidden righteous saints who keep the world from being destroyed on account of their virtue and piety (Sanhedrin 97b; Tractate Sukkah 45b). Shimon the Righteous said, "Upon three things the world stands: the Torah; the worship of God; and the bestowal of lovingkindness" (Pirke Avot 1:2):

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

God Suspended Mount Sinai |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Yet another legend states that when the children of Israel had gathered at Mount Sinai and took their places (literally) at "the foot of the mountain" (Ex. 19:17), God suspended the the mountain above their heads and said: "If you accept the Torah, all will be well. If not, you will be buried here." Nature stood still; the seas were quieted and not a creature stirred on the face of the earth, waiting for Israel's answer... It was quite different at Mount Sinai, however. God bent the heavens and shook the earth. Rivers suddenly ran backwards. The air reverberated with thunder and shofar blasts. Finally at about noontime the words "I AM THE LORD YOUR GOD" boomed out from the summit of Sinai. These words were understood not only by the terrified Israelites but by all the peoples of the earth (and even by the souls of unborn Jewish generations). In other versions of this story, the mountain was lifted up as a chuppah (wedding canopy) for the big day. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Black Fire on White Fire |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Then there is the legend (from Midrash Tanhuma) that the Torah was written with letters of "black fire on white fire" ("the flame alphabet"). According to some, this refers to the "two Torahs" -- the white fire is the "written Torah" (shebikhtav) whereas the black fire is the "oral Torah" (sheb'al peh). Others say the black fire denoted Divine Mercy while the white fire represented Divine Justice.... |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hebrew Letters as Spiritual Powers |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Still other legends concern the words and letters found in a Torah Scroll. For example, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev said, "There are 600,000 souls in Israel, and there are 600,000 letters in the Torah. Thus we can say that the Torah and Israel are one and the same, each Jew representing one letter of the Torah" (Kedushat Levi, Bamidbar). This is a puzzling statement, especially since we know there are 304,805 letters in a STA"M sefer Torah (kosher Torah scroll), with 79,847 words found in 5,845 p'sukim (verses). To those steeped in the Gnostic doctrines of Kabbalah, however, words and letters have special powers associated with them, and Torah mastery means tapping into secret knowledge of the Scriptures. The Zohar (a classic text of Jewish mysticism) puts it this way: "Just as wine must be in a jar to keep, so the Torah must be contained in an outer garment. That garment is made up of the tales and stories; but we, we are bound to penetrate beyond." Hence we see much writing about gematria, scribal oddities, "sod-level" mysteries, etc. Indeed, Torah is considered a sort of metaphysical "blueprint" for creation, and some Jewish mystics envision it as a sort of law that even God Himself must "obey." The words and letters of Torah -- regardless that they are now written in Ketav Ashurit (Aramaic square script) rather than the original Ketav Ivrit script) are seen as "divine emanations" that constitute the manifestation of God's will being exercised in the universe. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Aleph before Bet |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In another story about the Hebrew letters, the (personified) letter Aleph (×) complained that the Torah did not begin with him. "Master of the universe, I am the first of all letters. Why did you not create the world with me?" The LORD answered, "You must understand the entire world was created for the sake of Torah. When the time comes for me to give the Torah to my children, I will begin with you." The midrash goes on to explain that God made it up to Aleph by beginning the Ten Commandments: Anochi Adonai Elohekha ("I am the LORD your God"). The moral of the story is that the Holy One rates the giving of the Torah more highly than the creation of the universe (because the story of creation begins with the letter Bet (×Ö¼) in Bereshit). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What to make of all this? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What are to make of such stories and legends contained in Jewish tradition? Well, certainly these charming tales add color to our reading of the Torah, and they sometimes provide additional insight and commentary regarding the text itself. Understanding homiletic and imaginative interpretations of the Torah can help us become better attuned to the insights of those who know the writings of the Torah best, namely, the Jewish sages over the millennia. The parables, hyperbole, and other literary devices add emotional interest to our reading, allowing us to more fully savor the truths of Torah. A good story is a good story, and sometimes these can impart genuine truth to us. Maimonides had it right: the aggadot are not intended to replace the truths of the written Torah but to supplement our appreciation of them. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tentative Conclusion: Not Losing Our Way |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It should be clear that a distinction must be made between 1) reasoning from the written Torah and reaching consensus within the community, and 2) the notion that God Himself gave the oral Law as a divine commentary/explanation to Moses on Mount Sinai. These are two very different things, and how we decide upon this will affect the relative importance we give to the idea of oral Torah. Owe no one anything, except to love each other, for the one who loves another has fulfilled the law. For the commandments, "You shall not commit adultery, You shall not murder, You shall not steal, You shall not covet," and any other commandment, are summed up in this word: "You shall love your neighbor as yourself." Love does no wrong to a neighbor; therefore love is the fulfilling of the law (Rom. 13:8-10). The first occurrence of the word love in the Scriptures (××××, ahavah) (Gen 22:2) refers to a father's love for his "only" son who was offered as a sacrifice on Moriah (the very place of the crucifixion of Jesus), a clear reference to the gospel message (John 3:16). Some scholars have noted that the word ahavah comes from a two-letter root (××) with Aleph (×) as a modifier. The root means "to give" and the Aleph indicates agency: "I" give. Love is essentially an act of giving... The quintessential passage of Scripture regarding love (αγαÏη) in the life of a Christian is found 1 Corinthians 13: "Love seeketh not its own.." The antithesis of love is selfishness, the root of pride, fear, etc.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hebrew for Christians |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||