|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Learn Hebrew |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

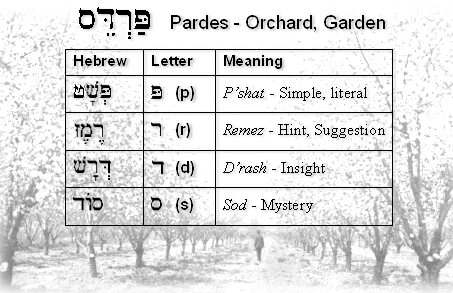

The Jewish sages typically allow inference within four main categories, with several levels of meaning coexisting sumultaneously within a given pasuk (verse):

|

|

The initials of these four general categories yield the acronym "PaRDeS" (meaning "orchard" or "garden"), said to be a reference to the ultimate restoration of mankind in the restored Garden of Eden or Paradise: |

|

|

Each of these four categories of exegesis is discerned based on literary cues within the texts of the Tanakh. In fact, the first step of studying our holy books is to discern each and every textual detail. Textual anomalies (such as oversized letters, undersized letters, backward letters, etc.) and apparent inconsistencies are not accidental or the result of scribal errors, but are considered sacred to the text itself. Therefore, once discovered, they must be explained. This is the starting point of all our textual exegesis.

|

|

As the face, so the eye... There are seventy ways of "looking" at the Torah. The Hebrew word for "eye" is 'Ayin. Ayin is one of the letters of the Aleph-Bet and has the numerical value of seventy. Also, the Tanakh indicates that 70 has a sacred significance:

Each generation of the study of Torah adds to the ongoing life of the Torah as it is lived in our people. |

||

|

Eilu v'Eilu Divrei Elohim Chayim |

|

Eilu v'eilu divrei elohim chayim |

|||||

|

"These and these are the words of the Living God" (Talmud Eruvim 13b) |

|||||

|

There are some arguments (regarding interpretation) that come from a person's pride, and there are others that are machloket l'shem shamayim, "a disagreement for the sake of Heaven"... Each of us needs wisdom and grace to discern which is which whenever we engage in such machloket (debate). The axiom eilu v'eilu appeals to a sense of charity we should exhibit whenever we encounter others who have views that differ from our own. |

|

An Exegetical Warning |

|||||||||

|

Regarding religious language there are three basic options. Univocal speech is that which has only one meaning; equivocal speech is that which has many meanings, and analogical speech has an "additional level" of meaning (i.e., ana + logos) that is similar to univocal but transcends it to apply to a different order or aspect of reality. Those who believe that Scripture is God's divinely inspired word generally hold to univocal and analogical reading of the texts, using grammatical-historical methods to discover the context and the original intent of an author, though with the rise of postmodern Christianity, equivocal reading has become fashionable. The problem with equivocal readings, however, is knowing where the semantic line should be drawn regarding significant interpretation and meaning. Postmodern Christianity tends to disregard the primacy of original intent in favor of the reader's intent to locate meaning in a given text, and that of course leads to subjective interpretations of various kinds. Generally speaking Jewish interpretive tradition quotes the Scripture: "One thing God has spoken; two things have I heard" (Psalm 62:11) to suggest that pluralistic interpretations are possible, and this has led to the saying shivim panim la'Torah, the Torah has "seventy faces," by which is meant that there are multiple facets of a given text and each has their place, though each will be grounded in the most basic level, called p'shat, or the plain sense of the original author, and any other facets inferred or derived will ultimately be consonant with that fundamental level. We also see this pluralistic approach in mystical readings of Torah with the division of four general semantic levels described using the term "Pardes," an acronym that stands for p'shat (plain sense), remez (allegorical sense), drash (moral sense), and sod (mystical or mysterious sense). Yeshua, of course spoke in parables and analogies all the time, and moreover as a prophet he also spoke mysterious and miraculous words that foretold the future, and so on, though his message of salvation -- that is, that he was to offer up his life as the sacrificial Lamb of God to repair for the sins of the world -- was intelligible to all "with ears to hear," even if sometimes people misunderstood his meaning |

|||||||||

|

Hebrew for Christians |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||