|

|

|

|

|

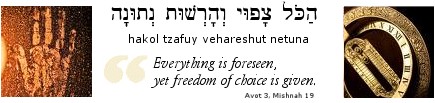

When we pray to the LORD, it's clear that we are not imparting to Him any information, since, as David points out, there isn't a word on our tongue that God hasn't already known in its entirety. This implies, of course, that God knows the future, since even before we collect our thoughts He knows what we will say (see Prov. 16:1). As Jesus said, our Heavenly Father knows our needs before we even ask Him (Matt. 6:8).

This is paradoxical to human reason, since if God already knows the future, how could it be otherwise? And yet we are nonetheless commanded to pray, to seek, and to walk by faith.

|

|

|

|

The first tenet of traditional Jewish faith is expressed as: "I believe with complete faith that the Creator, blessed be He, creates and guides all creatures, and that He alone made, makes, and will make all things" (Rambam, Commentary on the Mishnah).

|

|

|

|

God's sovereign care for creation ranges over the fate of the nations to the precise moment when a certain leaf falls to the ground from a particular tree in the forest. The number of the hairs on your head are numbered (Matt. 10:30).

|

|

|

|

|

|

The term hashgacha (ūöųĘū®ūüų░ūÆų╝ųĖūŚųĖūö) is sometimes used to refer to God's providential decrees. A midrash says, "God appoints an angel and tells it to cause a blade of grass to grow. Only then does that tiny blade flourish" (Bereshit Rabbah). There are no coincidences in God's universe; no "butterfly effect" apart from His hand. Often seemingly senseless or difficult circumstances disguise a hidden good. Therefore the person of faith affirms gam zu letova ("this too, is for the best"), acknowledging that everything that happens to us comes from heaven (see Rom. 8:28).

There is elaborate discussion about how God's decrees (gezerah merosh) do not violate man's free will (bechirah chofshit). In general, the sages decided that hashgacha refers to events we can't control, whereas it's our responsibility to make godly choices. This compatibilism became enshrined in the maxim: "Everything is foreseen by God, yet free will is granted to man" (Pirke Avot 3:19).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The late Henri Nouwen wrote, "I am beginning to see that much of praying is grieving," that is, realizing the fracture between the "is" and "ought" of our lives. Kierkegaard said that the purpose of prayer is not to influence God but rather to change the nature of the one who prays. When we get past our words -- our chatter, the insecurities that rise from our hearts, the cares of the day, even our hopes and dreams -- then we are sufficiently quieted to encounter God. It is then that we can truly listen and grieve over our lives in naked dependence upon God.

Psalm 139 has the tone of "hitbodedut" ŌĆō a spontaneous prayer of intimacy and earnestness that flows from personal experience. For David, God is contemporaneous and infinitely concerned with his personal life. The psalm begins with "O Lord, you have searched me and known me" (v.1) and paradoxically ends with "Search me, O God, and know my heart" (v.23-24). But why would David pray this way when he already understood that God knew his every thought?

There is an old saying that we are "only as sick as the secrets we keep." The LORD God is sovereign and knows everything about us, and that implies we have nowhere to hide (Heb. 4:13). David's desire is to live transparently before the LORD without self-deception. We must abandon, therefore, the "fig leaf" attempts to cover the truth about our lives and to welcome His examination of our hearts (Psalm 7:9; 11:5; 26:2, Prov. 17:3). When we do so, we can trust that He will lead us "in the way everlasting" (ūæų╝ų░ūōųČū©ųČūÜų░ ūóūĢų╣ū£ųĖūØ).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A related midrash...

|

|

|

|

A sage once saw a leaf fall from a tree and drift to the ground. He asked the leaf, "Why did you drop out?" The leaf answered, "I don't know. My branch shook me off." The sage then asked the branch why he shook off the leaf, but it answered that the wind did it. The wind, however, didn't have an answer as to why he blew the branch, except that he had been let loose by his angel. The angel, in turn, told the sage that he had received orders from

|

|

|

|

|

|

God Himself to get things windy. So the sage finally asked God, who told him to pick up the leaf. The sage lifted it from the earth to find a little worm sheltering in the shade the leaf created underneath. Everything -- even the falling of a leaf -- happens for a reason. It is up to us to recognize the handiwork of God behind it all.

|

|

|

|

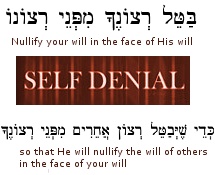

According to some of the sages (Kozhnitzer Maggid), when you are tempted by the evil inclination, you should pray: "I totally yield to Your will, God. Take my free will from me; I want neither free will not the reward for proper choice that it may bring me." If a man so prays, he can trust that God will nullify the will of others -- in this case, the evil one -- in the face of his will to serve God.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Theological Ruminations...

|

|

|

|

Logic, Sovereignty, and Paradox

The dilemma between God's foreknowledge and man's freedom can be expressed in this way. If God knows the set of all possible truths, then the future is not "open" to change, since at any given time (t) the truth status of a factual proposition (p) would already be known by Him. In other words, since God knows the truth of all counterfactual conditionals (i.e., statements like, "If your parents never met, you wouldn't have been born"), He also knows the truth status of all events in all possible worlds (i.e., possible sets of circumstances -- including the "world" wherein your parents never met), and He therefore also knows all events in the actual world (since that, of course, is a possible world). For example, if an omniscient God foreknew that I would do x rather than y at time t, then it is logically impossible for me to have done y rather than x (if I could have done y, then God would have been mistaken -- and therefore not omniscient).... So we can see that the idea of God's foreknowledge is related to the idea of divine predestination, at least from a logical perspective.

There are various attempts to work around this dilemma, including the (heretical) doctrines of "finite godism" (i.e., the denial that God is omniscient), full-blown theological determinism (i.e., the denial that man has any freedom at all), and various forms of compatibalism (e.g., the redefinition of foreknowledge to exclude time-referentiality (i.e., God is "outside of time") or the use of "modal logic" to allow God perfect knowledge of all possibilities without predetermining the outcome of events that depend on human choices, etc.). None of these solutions, however, is without its problems....

Traditional Judaism is essentially a "meritocracy" wherein a person is rewarded (by God) for his or her own achievements and spiritual growth. A Jew becomes tzaddik (a righteous man) through careful observance of the mitzvot given in the Torah (as well as by adhering to the various minhagim, chukkim, etc. of tradition). Since personal merit depends on making uncoerced moral choices, freedom of the will, personal responsibility, and tikkun olam (repairing the world) are stressed (and the idea of divine predestination is rejected). Hence the sages say that a man can "recreate himself through the spiritual metamorphosis of teshuvah" (repentance, turning to God). In short, despite the acknowledgement that God's hand is over all the details of life (i.e., the Lord as Creator and the principle of sufficient reason for all of creation), traditional Judaism maintains that prayer, charity, and teshuvah can sometimes "overturn" the divine decrees (gezerot merosh), at least regarding the final outcomes that pertain to human beings.

There are various problems, however, with this viewpoint (or any viewpoint that maintains the way to please God is on the basis of human "works of righteousness"). First of all it must be conceded that any idea of human freedom be qualified by a host of historical, genetic, sociological, and cultural conditions that limit the idea of uncoerced human volition. For example, we are not free to choose who our parents are, what our genetic background/DNA code is, when and where we were born (i.e., our time and place in history with all that entails), and so on. Regarding the physical world and its laws, we are also not free to defy gravity by jumping to the moon, to live without eating or drinking, or to make our stature "a cubit higher" than it is (Matt. 6:26). "The Ethiopian cannot change his skin color nor the leopard his spots" (Jer. 13:23). Regarding the ideational world, we are not free to make 2+2=5, to "square a circle," or to deny the logical laws of identity (a=a) or non-contradiction.

In the Brit Chadashah, the word "predestination" is proorizo (ŽĆŽü╬┐╬┐Žü╬╣╬ČŽē), a Greek compound comprised of ŽĆŽü╬┐- (before) and oŽü╬╣╬ČŽē (appoint, decree, limit [as in a horizon]). This word occurs in Rom. 8:29,30; Eph. 1:5,11, Acts 4:28 and 1 Cor. 2:7 (note that this word is different than the word used for divine foreknowledge (ŽĆŽü╬┐╬│╬╣╬ĮŽēŽā╬║Žē)). Predestination denotes that God has determined certain things to occur ahead of (our current) time -- for example, the facts surrounding prophecies, but more personally, that God sovereignly chooses (elects) certain individuals to be saved.

Regarding the idea of God's election, Yeshua told us that we must be "born again" in order to "see the Kingdom of God" (John 3:3). This spiritual rebirth is a divine act, "not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God" (John 1:13). Yeshua also told his followers: "You did not choose me, but I chose you and appointed you" (John 15:16). He also said, "No one can come to me (╬┤Žģ╬Į╬▒Žä╬▒╬╣ ╬Ą╬╗╬Ė╬Ą╬╣╬Į ŽĆŽü╬┐Žé ╬╝╬Ą) unless the Father who sent me draws him" (John 6:44, see also John 6:65). We are not chosen by God (eklektos) because we chose Him, but rather because He chose us. Plainly put, a person is "saved" by being drawn by God's sovereign design and love (John 6:44). God is the initiator of the relationship; He is the Master and Ruler over all flesh. If there is revelation from heaven, it is Heaven's absolute prerogative to bestow it on Heaven's own terms...

The state of soul before spiritual rebirth is described as a sort of "living death." We were dead to things of the Holy Spirit, unable to respond to the truth of God, incapable of gaining access to life. Our carnal minds were at war with God. We were powerless to impart spiritual life to ourselves since this life is ontological -- a real mode of existence -- that is imparted to us solely by God Himself. Spiritual rebirth is not an exercise in moral reformation or self-improvement. We don't get to "elect ourselves" into the Kingdom of Heaven or become a child of God by raising our hand at a prayer meeting or performing various meritorious acts... No. New life is given through the exclusive agency of God Himself. God alone gives salvation to the soul... God alone is the Master of the Universe and everything belongs to Him -- now and forever -- and that most especially concerns those for whom He came to redeem (see John 6:44, 65).

The Apostle Paul taught that God "chose us [╬Ą╬║╬╗╬Ą╬│╬┐╬╝╬▒╬╣] in the Messiah before the foundation of the world" (Eph. 1:4). God called you by name -- before He created the very universe itself. "God has chosen you from the beginning for salvation through sanctification by the Spirit and faith in the truth" (2 Thess. 2:13).

In speaking of the remnant of Israel (she'arit Yisrael) that retained covenant with God, Paul contrasts the "children of the flesh" with the "children of the promise." Paul used the case of the birth of the twins Esau and Jacob to demonstrate God's sovereign election. "Though they were not yet born and had done nothing either good or bad - in order that God's purpose of election might continue, not because of works but because of his call - she (Rebecca) was told, 'The older will serve the younger.' As it is written, 'Jacob I loved, but Esau I hated.'" Paul anticipated the objection that God's election of Jacob over Esau seems arbitrary -- perhaps even unfair -- by reminding us of God's words to Moses: "I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion." He then follows this up with the statement: "So then it depends not on human will or exertion, but on God, who has mercy" (Rom. 9:15-16).

In the end, we are left with paradox. On the one hand, God alone is the sole agent for salvation, but on the other hand we are responsible (at least from the phenomenological point of view) for genuinely responding to God's call... God elects and predestines who will be saved and we must personally choose to receive the Mashiach and follow Him with all our hearts. We are sovereignly chosen to freely choose to live for God...

Reflection on the doctrine of God's omniscience (like other essential doctrines of our faith) leads to paradox and tension within our human understanding (by means of which we are deepened in our surrender to the LORD and His will for our lives). This paradox is restated in Philippians 2:12-13: "Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling (your part), for it is God who works in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure" (God's part). As Yeshayahu ha-navi (the prophet Isaiah) wrote: "For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, declares the LORD. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts" (Isa. 55:8-9).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some Practical Thoughts...

|

|

|

|

Freedom from the power of sin; Freedom for the glory of God

Many people think of "freedom" as the ability to do what they want, when they want to, and according to their own immediate gratification. "Doing your own thing" is the catch phrase of those who want to be able to pursue their own desires (i.e., lusts) without resorting to any source of moral or spiritual authority...

This worldly freedom is not true freedom, however. Yeshua told us that "whoever commits sin is the slave (╬┤╬┐Žģ╬╗╬┐Žé) of sin" and went on to say that "if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed" (John 8:34-36). True freedom is moral and spiritual rather than physical. Freedom has to do with the ability of the will to choose according to the light of moral and spiritual truth. This freedom, however, is further constrained by the nature or quality of being itself. In other words, freedom is a product of heart that acts according to its particular nature....

Augustine of Hippo (d. 430 AD) was one of the first to formally relate the state of soul to freedom with regard to sin. These are defined, respectively as:

- Able to sin (posse peccare) - This is the original state of mankind, before the Fall. Man was created with the ability to sin (posse peccare) and also the ability to not sin (posse non peccare). Augustine wrote: "In Adam's original sin, man lost the the power not to sin but retained the power to sin -- which he continues to exercise.

- Unable to not sin (non posse non peccare) - This is the state of the "natural man" after the Fall. For the unregenerate soul it is impossible to not sin (Rom. 3:10-12). The Apostle Paul wrote that the carnal mind is hostile toward God and cannot please Him (Romans 8:7-8). "Wherefore, as by one man sin entered into the world, and death by sin; and so death passed upon all men, for that all have sinned" (Rom. 5:12).

- Able to not sin (posse non peccare) - This is the state of the regenerated soul that is undergoing the process of progressive sanctification. This is not a state of "sinless perfection," since Scripture makes it clear that followers of the Messiah do sometimes sin (1 John 1:8-9, 2:1; James 3:2, 5:16; Rom. 7:18-19; Matt. 18:7, etc.).

- Unable to sin (non posse peccare) - This is the state of the glorified soul. Augustine wrote: "In the fulfillment of grace, man will have the posse peccare taken away and receive the highest of all, the power not to be able to sin, non posse peccare.

The logical possibilities might be easier to understand when seen in the following table:

|

Before the Fall

|

After the Fall

|

After Regeneration

|

After Glorification

|

|

able to sin

|

able to sin

|

able to sin

|

able to not sin

|

|

able to not sin

|

unable not to sin

|

able to not sin

|

unable to sin

|

|

In this schema, freedom is understood as man's ability to choose according to the light of spiritual/moral truth based on its current state of grace (i.e., freedom must be understood as relative to the current state of the soul in relation to God's salvation). When God created man, he was in a state of "innocence" wherein he was entirely free to chose either to sin or not. After Adam sinned, however, death entered into the human race and the state of soul of all the descendants of Adam and Eve thereby became "unregenerated" (i.e., spiritually dead). Man's ability to choose was vitiated and he became enslaved to self-interest, driven by fear, and engulfed in spiritual darkness. His state of being as a "natural man" precluded him from apprehending the truth and living according to its light. After spiritual rebirth and "regeneration," however, the soul is "made alive" (╬ČŽē╬┐ŽĆ╬┐╬╣╬ĄŽē) by the Holy Spirit and made free from the "law of sin and death," i.e., the power of sin. This does not mean, however, that the regenerated soul is able to attain a state of moral perfection and entirely cease from sinning, since the process of sanctification involves apprehending the soul's new identity through the ongoing practice of faith. Finally, the state of soul in olam haba -- the world to come -- is one wherein the soul is "glorified" and accorded the power both not to sin and the everlasting grace to be unable to sin against God. This is the heavenly state - the Holy Mountain - where the very presence of sin will forever be eradicated.

Through His sacrifice as Seh ha-Elohim (the Lamb of God), the Messiah Yeshua purchased our freedom by redeeming us from the curse of the law's judgment -- and therefore redeemed us from slavery to the power of sin and death. Analogous to the first Passover in Egypt, we are now free from the stranglehold of Pharaoh (a type Satan) and the tyranny and oppression he enforces on those who are his captives. We no longer are obligated to live under the oppression and slavery of fear, since even death itself has been vanquished and we are just beyond the veil of life in the realm of heaven.

Since therefore the children share in flesh and blood, he himself likewise partook of the same things, that through death he might destroy the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil, and deliver all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong slavery (Heb. 2:14-15).

For you did not receive the spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received the Spirit of adoption as sons, by whom we cry, "Abba! Father!" (Rom. 8:15)

...where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom (2 Cor. 3:17).

For freedom Christ has set us free; stand firm therefore, and do not submit again to a yoke of slavery (Gal. 5:1).

For you were called to freedom, brothers. Only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for the flesh, but through love serve one another (Gal. 5:13).

Live as people who are free, not using your freedom as a cover-up for evil, but living as slaves (╬┤╬┐Žģ╬╗╬┐╬╣) of God (1 Peter 2:16).

There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear. For fear has to do with punishment, and whoever fears has not been perfected in love (1 John 4:18).

Beloved, our very salvation is about freedom -- the freedom to become the very children of God (John 1:12, 1 John 3:1). May God help you live in His freedom today....

<< Return

|

|

|

Hebrew for Christians

Copyright © John J. Parsons

All rights reserved.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|